Everyone is aware that worm control is a very important part of equine management and practices regarding frequency and method of de-worming have changed in recent years. For most people on big yards these days, submitting faecal samples to be tested for worm eggs is normal practice but what is quite often forgotten is that this simple test will not give you any information regarding the tapeworm burden of your horse.

Tapeworm, or Anoplocephala perfoliata, require an intermediate host to complete their lifecycle. Grazing horses will ingest forage mites which are normally found on the grass, these forage mites are infected with larval tapeworms. Once these larval tapeworms reach the intestine, they will mature into adult tapeworm and begin to produce eggs themselves. These eggs develop in body segments called proglottids which, once ready, are detached from the body of the tapeworm and passed out onto the pasture in faeces. Once on the pasture, the proglottids disintegrate over time and release the eggs, this process is why eggs cannot be picked up on routine faecal sample screening as they are not yet free within the faeces. The free eggs are ingested by forage mites and develop into tapeworm larvae which can be eaten by the grazing horse and the cycle continues. Within the horse, the cycle takes roughly 1 to 2 months and on the pasture, between 2 and 4 months.

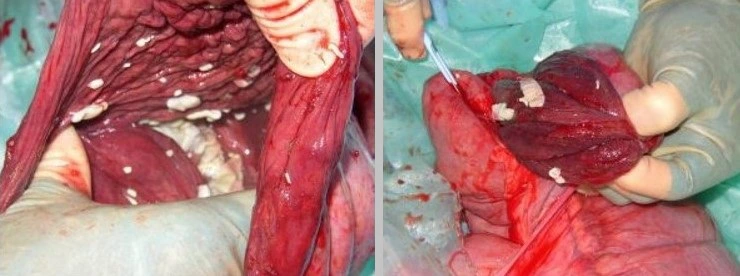

Tapeworms within the horses gut tend to congregate in certain areas of the intestine, these are typically the walls of the caecum (a large blind ending sack at the beginning of the large intestine) and at the junction of the caecum and the ileum (the last part of the small intestine). Tapeworms themselves are large worms, they can be up to 10 inches long and half an inch in width, this means that by sheer number they can cause blockages but also will attach themselves to the intestinal walls which can cause extreme discomfort. Another problem that heavy tapeworm burden can cause is caecocolic intussusception which in laymen’s terms is telescoping of the caecum into the colon, this is a very serious condition requiring very involved surgical intervention and even with surgery, survival is not guaranteed.

Determining whether your horse has tapeworm is by a blood test or a saliva test, both are relatively simple and will give reliable results. Testing before treating is still very important, some may argue more important in the case of tapeworm as there are only two drugs available that are known to effectively rid your horse of a burden and resistance could be catastrophic. Testing can be done at any time of year and results are usually returned quickly, testing more than once a year can give false positives since the test shows the intensity of the bodies response to the infection and can take time to reduce if the worm burden was high.

Tapeworm does not exhibit a huge degree of seasonality like some other worm lifecycles and so treatment at any time of year will be effective. This being said, risk is greater following prolonged grazing periods and so it is often suggested that horses are de-wormed for tapeworm at the end of summer. There are two drugs that are effective at killing tapeworm, praziquantel which is often combined with other drugs and pyrantel. Pyrantel is partially effective at the usual dose but a double dose increases the efficacy to 95%. Treatment of the horse is a vital part of managing tapeworm burden but as with all worming protocols, pasture management is also vital – regular poo-picking, rotational grazing and cross species grazing are all good practices to put into place.